Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

Sophia moves into an aging apartment with her young daughter Helena. The building sits in a narrow lane in an Italian town that still keeps older eras trapped in its plaster and wood; light pools in the stairwell and the elevator smells faintly of oil. At night Helena tells her mother that a woman lives in the closet of the small bedroom she sleeps in, and she calls the woman the Tooth Fairy. Sophia soothes Helena, tells her the sounds come from pipes and mice, but the girl cries quietly in the dark and draws pictures of a smiling woman with nothing but gums where teeth should be. The first time the Tooth Fairy appears to Sophia herself it is at two in the morning; the woman stands in the doorway of the apartment, thin dress clinging to a body that remembers warmer decades, and she smiles with a mouth stripped bare of teeth. Sophia feels cold clamp at her throat and the woman says nothing; she only stares, head cocked, and then disappears into the thin city night.

Helena begins to change. She wakes in terror, screaming that the Tooth Fairy reached inside her mouth. Her neck carries small bruises that Sophia attributes to fingernails; Helena refuses to open the closet door where she sleeps and insists her bed is safe only because of a line of salt Sophia sprinkles the first night to humor her. In daytime Helena flinches at sudden movements and refuses to talk about the woman. Over several weeks the visits intensify. One night the Tooth Fairy appears in Helena's room and crouches at the foot of the bed, fingers working the hem of the blanket like a cat disturbing prey. She smiles and leans so close that the girl can smell old milk and iron. Helena wakes with blood at the corner of her mouth and teeth loosened; she clutches at her gums and howls until Sophia carries her into the bathroom with shaking hands and presses gauze to Helena's bleeding lip. After that night Helena stops sleeping inside the apartment at all. She begins to sleep in Sophia's arms during the day and cries when Sophia moves away.

Sophia seeks help. Doctors examine Helena and find no physical illness that explains her terror and the loosened teeth; a child psychiatrist suggests institutional care to stabilize Helena's anxiety. After a particularly violent episode in which Helena screams that the Tooth Fairy has taken her teeth and that the woman is hungry for them, Sophia yields to the medical recommendation. The hospital staff in their white scrubs and soft shoes lead Helena into a long corridor with pictures on the walls. The child is sedated for a time and then admitted to a psychiatric ward where nurses strap a thin bracelet to her wrist. One year follows in which Sophia visits through glass and sits on a plastic chair while Helena looks at her with large, frightened eyes that sometimes show a child conversing with someone only she can see. Sophia signs the forms and leaves the building each time with her shoulders heavy and jaw set to hold back a grief that tastes like iron.

During Helena's confinement Sophia refuses to accept that the visits will end on their own. She believes the woman in the closet is not a figment of a damaged child's imagination but a spirit bound to the apartment by something more particular. Sophia begins to dig into the building's history. She goes to the municipal archives, turns brittle pages, and learns the apartment's name under a faded ledger: the unit had once been occupied in the World War II era by a family named Batista. In a dusty ledger kept by a local militia officer Sophia discovers an old note and, later, a cracked leather reel-to-reel tape labeled with a date decades old and the name Batista. She takes the tape home, but the player in her living room is silent. With the help of a repair shop owner who remembers the old militia, Sophia finds another reel-to-reel and presses play.

The tape contains a confession recorded in a voice thick with tobacco and regret. Batista speaks directly into the microphone with a cadence like a man repeating a suicide note. He explains that his wife had once been a beautiful woman, that she smiled too freely and that he watched the way other men's eyes followed her. He says the militia made up a story about wolves to explain a string of disappearances among the village children. On the tape Batista admits that the truth was uglier: his wife was ill and she lured children into the woods to feed them. He talks about the day he discovered what she had done--how he found the remains of a child under the roots of an ash tree--and how she laughed and tried to say the children tasted like honey. Batista's voice on the tape grows ragged with a confession of dread as he explains that, when he confronted his wife, she turned on their own daughter.

Sophia listens as Batista describes the sequence in a minute, horrifying detail. He says his wife killed the children, including their daughter, by pulling them into the kitchen and tearing at them. On that reel Batista says he could not forgive her. He details how he ripped out every tooth from his wife's mouth one by one with pliers in the kitchen and then locked her in the same closet that now sits in Sophia's apartment. He tells the microphone that he killed her to stop her, that he slit her throat to end what he saw as an abomination. After he finishes speaking Batista explains that fear of her return led him to hide the teeth, to scatter them or store them so the woman's spirit could not be complete. His voice on the tape trembles when he admits to covering up the truth with the militia, claiming wolves to prevent the town from knowing a mother could feed her children to herself. The recording ends with Batista saying little more than that he hopes, in time, the dead will forgive him.

Sophia reacts to the tape with disbelief, and then with a slow, building horror. She rewinds the reel, plays it forward again, and pauses on a strange phrase: Batista describes locking his wife in that very closet and leaving her to starve before killing her and hiding her teeth. Sophia goes back to the apartment and kneels outside the closet Helena once claimed as her room; she slides a thin crowbar under the warped floorboard beside the closet and pries. She finds, beneath the floorboards and an old piece of cracked linoleum, a small metal tin. Inside sit dozens of human teeth, yellowed at the roots and gray with age. Sophia holds them with gloved hands like relics and remembers Helena's drawings: rows of empty gums and a smile that never rested. She wraps the tin in cloth and carries it through the apartment until she can no longer stand the place's temperature.

But Sophia does more than keep the teeth as evidence. She believes the woman's spirit remains hungry because her teeth were removed in life, because something whole was taken from her. In the basement of the building she finds a place to perform a ritual of return--a place between furnace pipes and a stack of old crates that smells of coal and damp paper. Sophia opens the tin and lays each tooth on a cloth, smoothing the gums with slow fingers as if sewing a mouth shut. She does not speak aloud; she only arranges the teeth in sequence, from the smallest incisors to broad molars. Then she leaves the basement and walks up three flights of stairs to the closet of the apartment. She forces the lock and sets the teeth inside the hollow of the closet, placing them in a small ceramic bowl and covering them with a scrap of Helena's blanket she has kept since her child's first night there. After Sophia returns the teeth she cannot say she feels something shift immediately, but for the first time in months Helena sleeps through an entire night without screaming.

Helena returns from the institution after a year. The hospital gives her a pale certificate and a list of medications, and a nurse hands Sophia a small packet. On the apartment stairs Helena walks in front of her and runs her fingers along the banister like a child testing gravity. At dinner that night Helena eats with a steadier hand than before and tells Sophia about school and a new teacher. For the next weeks Helena laughs sometimes and goes outside with other children. Sophia watches and allows herself a guarded relief. She still sweeps salt along the closet threshold, but she does not feel the same immediate dread at bedtime. Helena sleeps through a storm and wakes without tearful eyes. Sophia believes the returned teeth have ended the visits.

Even as domestic routine resumes Sophia cannot shake the tape. She replays Batista's confession until the edges of the recording blur, and she begins to suspect the town's quiet is heavier than ordinary. She receives a call from the old militia officer, who asks to meet; the man presses his cigarette between his lips and tells Sophia that the village buried its dead quickly in the years after the war and that families preferred quick explanations. His eyes stay on the street as he speaks, and the officer hands Sophia a sealed box of archival footage he says was declassified. Inside are more tapes--some minutes of local patrols, some of family gatherings and a single shaky film of a small girl playing near an ash tree. Between frames Sophia sees a boy run into the bushes and never come back. She stops the projector and sits with her palms over her mouth until her skin feels like ice.

Late one night, when the city hum is quiet and the washer outside clanks its final cycle, Sophia cannot stand to sit still. She locks the apartment door, takes Helena's hand and goes out into the night to look for any trace of the children Batista mentioned. She walks the alleys that border the older part of town and watches the hedges under street lamps. At a park she finds a patch of earth recently disturbed and small bones scattered like pebbles in the dirt. Sophia stoops, touches one with a fingertip, and overturns another. A child's jawbone sits in the hollow of the root of a low tree, yellowed and foolishly small. Sophia staggers backward and then moves on down a footpath until she finds a small clearing strewn with the remains of what were once small bodies--buttons from coats, a shoe missing its mate. The ground is soft with the diggings of animals and with age. She vomits onto the path and waits as a man with a flashlight and a farmer's hat comes up behind her and shines light on the bones.

Sophia confronts the farmer and asks him if he remembers a woman who smiled too widely. The farmer's mouth pulls into a thin line; he says people around here do not like to speak of things that make them restless. He tells Sophia that the old militia kept records locked and that many people left or made themselves forget. He says Batista took care of his own shame in the same way that many in the town took care of their own: by pretending wolves had come down from the hills. Sophia turns the farmer's flashlight toward the sky and then back to her hands and finds an old tooth lodged in the dirt. She recognizes it instantly by its root. The thought that she carries to the police and to the municipal office is simple: the children do not belong in the earth of wild animals; they belong to mouths that once fed and to a home that still smells like bread.

Sophia's searches grow more desperate. She visits the place where Batista once lived and finds the house door cracked. Inside she finds a sink stained with dark marks and a range with rusted utensils. She opens the closet that for decades has been sealed and finds the floorboard she first pried up. Under the board there are fresh signs of disturbance, as though someone has been digging to reveal what was hidden. Sophia brings a spade and digs until the metal clinks against tin and bone. She pulls out fragments of rib and a child's hair bow. She holds them in the light and knows, without doubt, that the woman whose teeth Sophia returned in the basement fed on children in life.

The night Sophia reaches the apartment where Helena sleeps she walks softly, keys in hand as if in prayer. She flings the door open and runs to Helena's room. She sees the closet door slightly ajar and opens it. She finds only a small ceramic bowl set on the floor with a matted scrap of blanket inside; the teeth are gone from the bowl. Sophia searches the apartment and the stairwell and outside under the eaves and in a trash heap near the bakery. In the trash she finds a tiny shoe with a bite taken out of it and a smear of congealed blood on the rim of a bakery crate. She runs, breathless, back through alleys and finds the pathway to the hospital, the rails of the river, and then a side street where she sees other parents standing in doorways and whispering.

Sophia knocks at the institution's heavy door and is admitted because she is Helena's legal guardian. She runs through the sterile corridors, passes nurses at their stations and an orderly wheeling a cart. In the hallway she sees open-ward doors and inside children sleeping like hunched birds. A nurse holds back an anxious father. Sophia asks where Helena is and the nurse directs her to a windowed room in the far wing. Sophia runs to the window and looks in. The room is empty except for a small cot and a smear of recent red along the sheets. Sophia's fingers find the handle and the door yields; she steps inside, finds Helena's blanket on the floor, and a patch of the wall near the headboard chewed ragged. Sophia calls Helena's name and hears nothing but a hum.

At the same time elsewhere in the town other parents scream. Sophia hears one thin, jagged sound and runs out into the courtyard. She sees figures clustering at the end of a corridor. A man in a gray coat points and says that someone has been seen in the hallway windows. Sophia climbs the steps and reaches a landing that looks down into a long row of rooms. In one window, across from her, something apart from the moment and terrifying as an echo stands in the glass. For an instant Sophia believes it is Helena and then realizes that the image is not the same child who came home from her year in the hospital. The figure in the glass is pale, hair matted, and the right side of its face is missing a large chunk of flesh. The cheekbone juts like a knife; the mouth is slack and swollen where the Tooth Fairy has bitten. The figure presses its face to the pane and, with a lazy, animal hunger, looks at Sophia. The mouth opens and closes on empty air.

Sophia screams a sound that carries across the courtyard and into the stairwells. Staff rush out with flashlights, and a doctor takes hold of her shoulder and tries to pull her back, but she breaks free and climbs the stairs two at a time until she reaches the window. People gather below and call to one another, and in the reflection of the glass Sophia sees herself and, superimposed, the face of a child robbed. She sees the missing flesh in bright contrast to the fluorescence of the corridor. Helena, pale and broken, looks out with eyes that still search the world for her mother. Sophia reaches the glass, presses her palm to it, and the child presses back. The sound that slips from Helena's half-mouth is not a cry so much as a small, curious rasp.

Nurses pull Sophia back and someone covers her mouth with a hand. They tell her to sit on a bench and paramedics bring a wheelchair. Sophia tries to speak; the words are needles. She points up at the window where the child stares as if carved, and a nurse says in a voice that tries to steady itself that they will bring Helena downstairs. The nurse's words, measured and rehearsed, say they cannot extricate a patient who is in the window until the doctor allows it. Sophia refuses to wait. She wrests free and runs to the nurse's station, where she finds a staff member who has seen the old reel-to-reel. The staff member moves quickly, unlocking a side door and warning Sophia to hold back, but the hallway beyond houses only empty beds and the wet scent of antiseptic.

Sophia reaches a small sitting courtyard beside the hospital and collapses on a bench. She sits with her hands on her knees, hair wild, dress askew. A guard brings her a blanket and speaks quietly until she calms enough for the police to take a statement. The guard's voice is small and legal. He asks if she can describe the child she saw and if she recognizes Helena. Sophia says she does: the child in the window was her daughter, but the right side of the girl's face was missing a smear of flesh, as if bitten away. The guard writes slowly and asks if Sophia believes someone attacked Helena. Sophia only knows that the teeth she returned are gone and that the woman on Batista's tape fed children in life. She tells the guard everything she found in the cellar of the apartment and in the park and what Batista said on the old reel.

When Sophia stands to leave the courtyard she sees, in the glass of another window, an image of Helena that seems to be rigged into the world like a film negative. The child sits at the far window with an absence of expression and a bite taken out of the face where cheek and jaw should be. Sophia walks closer until the bloodless hand of the child smears fog onto the glass. The nurse who follows her says there is nothing to be done until a full team examines the patient; Sophia asks that they be allowed to talk, to touch, to restore in some way the child who once sat on her laps and learned to whistle. The nurse tells her the patient will be sedated and released only if the doctor deems her fit. The words have an official calm as if the situation can be solved with a form.

Sophia does not file complaints or petitions that week; she sits instead in the courtyard most days and watches the windows. She holds in her hand a photograph of Helena before the visits, of a child with two unmarked cheeks and a dimpled chin. The photograph grows creased with use. On a late afternoon, after a rain has silvered the pavement, a cluster of staff open a window across from the courtyard and carry the child out wrapped in sheets. The nurses move like people shifting a fragile relic. Sophia stands and rushes forward, shoving through the knot of visitors. As she reaches the stretcher the sheet is whipped away by a small gust from the open window and Sophia sees Helena's face for the last time in the film. One side of the girl's face has a jagged, fresh wound where skin has been removed in a crescent and the cheekbone shows pale and raw. The wound is glistening and a piece of torn flesh dangles at the edge of the jaw, wet and dark.

Sophia screams and then goes still. The nurses gather and speak in low voices as they strap the sheet more tightly and wheel Helena into a different wing for emergency surgery. Sophia follows them into a corridor and places her hand on Helena's small wrist. The pulse beneath is faint and fast. She smells copper and thinks of the teeth she returned in the closet. She looks up through the windowless corridor and sees, for an instant through the glass, the outline of the woman who had once been Batista's wife bending at the mouth of the closet and smiling with her gums empty. The woman looks at the mother and her expression is not one of regret but of satisfied hunger.

Helena is taken into surgery. The staff use antiseptic and machines and speak in clipped tones about grafts and infection. Sophia signs forms and prays silently in her body like a person counting steps. The doctors work through the night. In the early hours a surgeon steps out and tells Sophia that they managed to stabilize the wound but that some tissue is lost and that reconstructive procedures will take time. Sophia nods, too tired to ask more. They wheel Helena into a recovery room and Sophia sits on a vinyl chair, hands folded so tightly her knuckles are white.

The film ends not with resolution but with a long, stark quiet. Sophia sits under a leafless jacaranda in the institution courtyard. Her face is numb and hollowed as if carved by grief. She watches shadows move across the cobbles and thinks of the tin of teeth she once pried from the closet floor. A nurse passes carrying a tray and glances at Sophia with the polite sorrow of someone who has seen too many people break. Sophia lifts her head as if to look back into the building. In a distant window of the ward she sees an image that makes her stomach tilt: Helena's face, pale and scarred, appears as if in a projection on the glass. The child's mouth is slack and one large piece of flesh is missing from her face. The image holds for a long breath; then it recedes like a tide and is gone. Sophia remains seated, hands in her lap, and does not move as the courtyard empties and the light shifts toward dusk. The camera pulls back to show the asylum and the city beyond, and the last frame holds on Sophia's face, eyes open, fixed on a window whose occupant will not be restored to what she once was.

What is the ending?

I couldn't find any specific information about a movie titled "The Haunting Of The Immaculate Nurse" produced in 2024. The search results seem to refer to a different movie, "Immaculate," which involves themes of horror and religious mystery. If you are referring to "Immaculate," I can provide a detailed summary of its ending.

However, if you are indeed looking for "The Haunting Of The Immaculate Nurse," I recommend checking other sources or databases for accurate information.

If you would like, I can provide a detailed summary of the ending of "Immaculate" instead:

Short Summary: In "Immaculate," Sister Cecilia discovers she is pregnant despite being a virgin, and the convent believes the child is the second coming of Christ. As Cecilia's pregnancy progresses, she becomes increasingly fearful and resentful of the convent's sinister intentions. She attempts to escape but is thwarted. Eventually, Cecilia gives birth in a catacomb, kills the baby, and escapes.

Expanded Answer:

The ending of "Immaculate" unfolds with Sister Cecilia, played by Sydney Sweeney, deeply entrenched in a nightmare of her own faith. As her pregnancy advances, she becomes more desperate to escape the convent, fearing for her life and the true nature of her unborn child.

Cecilia fakes a miscarriage using a dead chicken in an attempt to be taken to a real hospital, but Father Tedeschi discovers her plan and stops her. This event marks a turning point in Cecilia's resolve to take drastic action against the convent.

In a series of violent confrontations, Cecilia attacks several key figures, including Mother Superior and Cardinal Franco. She also sets fire to the lab where Father Tedeschi's research is stored, trapping him inside. However, Father Tedeschi manages to escape the burning lab and pursues Cecilia into the underground tunnels of the convent.

As Cecilia navigates the tunnels, she discovers the body of Sister Gwen, a nun who had been brutally silenced by the convent. Cecilia's labor pains intensify, and she is eventually pinned down by Father Tedeschi, who attempts to deliver the baby via C-section. In a final act of desperation, Cecilia kills Father Tedeschi by stabbing him in the head with a holy nail.

With Father Tedeschi dead, Cecilia manages to escape the tunnels and gives birth outside. The baby, however, is not human, and its cries are unnatural. Horrified, Cecilia kills the baby with a boulder, marking the end of the film.

Throughout the climax, Cecilia's character evolves from a devout nun to a woman driven by survival and a desire to protect herself from the sinister forces surrounding her. The fate of the main characters is sealed in violence and tragedy, with Cecilia emerging as the sole survivor, forever changed by her experiences.

Is there a post-credit scene?

I couldn't find any specific information about a movie titled "The Haunting Of The Immaculate Nurse" produced in 2024. The search results primarily discuss a movie titled "Immaculate," which does not have a post-credits scene. If you are referring to a different film, please provide more details or clarify the title.

If "The Haunting Of The Immaculate Nurse" is indeed a different film, I would recommend checking reputable movie databases or reviews for accurate information regarding any post-credits scenes.

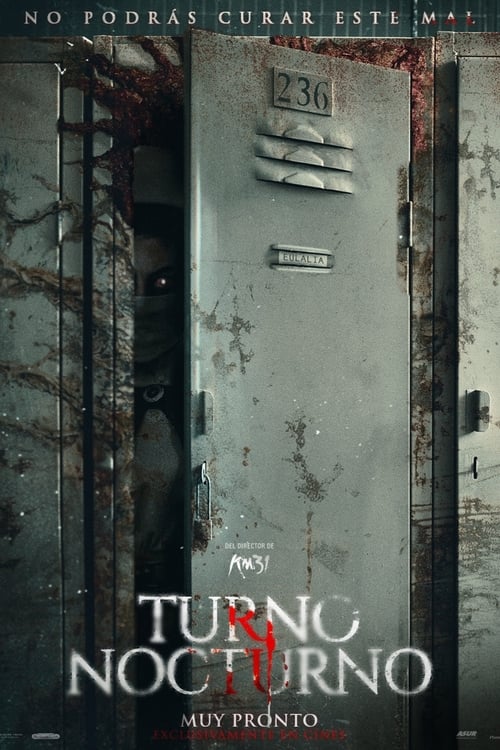

What motivates Rebecca to take the night shift job at the hospital?

Rebecca is motivated to take the night shift job at the hospital likely due to her need for employment and possibly a fresh start, given her past of family violence. The job offers her an opportunity to work in a new environment and potentially escape her personal struggles.

How does the character of Hortencia influence Rebecca's experience at the hospital?

Hortencia, the chief nurse, influences Rebecca's experience by warning her about getting too close to and complying with the paranormal activity of La Planchada. This warning adds to the tension and mystery surrounding Rebecca's night shifts.

What role does Dr. Sánchez play in Rebecca's story?

Dr. Sánchez is portrayed as condescending towards Rebecca, which adds to her stress and challenges at the hospital. His behavior contributes to the difficult environment Rebecca faces during her night shifts.

How does Rebecca's past of family violence impact her interactions with other characters?

Rebecca's past of family violence likely makes her more guarded and sensitive to the behaviors of others, such as Dr. Sánchez's condescension and the sexual harassment by another doctor. This past may also influence her reactions to the paranormal events she experiences.

What are the rules that Rebecca is told to follow during her night shifts?

Rebecca is told to follow specific rules during her night shifts, including not forgetting anything, not getting involved with the staff, and never falling asleep. These rules are meant to help her navigate the paranormal occurrences at the hospital.

Is this family friendly?

The Haunting Of The Immaculate Nurse, produced in 2024, is not family-friendly due to its horror genre and themes. Here are some aspects that might be objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive people:

-

Violence and Blood: The film involves intense and potentially disturbing scenes, including violence and blood, which could be unsettling for younger viewers or those sensitive to graphic content.

-

Ghostly Elements: The presence of a ghost nurse and supernatural events may be frightening for children or those who are easily scared by paranormal themes.

-

Emotional Trauma: The protagonist has a past of family violence, which could be emotionally challenging for some viewers, especially if they have experienced similar situations.

-

Mature Themes: The movie explores mature themes, including domestic abuse and possibly sexism, which might not be suitable for younger audiences.

Overall, while the film may have some interesting elements, its content is geared more towards adult viewers due to its dark and potentially disturbing nature.